Old-time fiddling: Playing the ‘wrong’ way

I feel that my involvement in old-time fiddling has proven extremely beneficial for both my playing and sense of musicianship in general. In order to justify this assertion, I would like to examine a few aspects of old-time fiddling and make a few short comments. These comments will be based on my short old-time fiddling experience and some general views on skill development and the acquisition of knowledge. I am aware of course that by no means are they valid among all practitioners of old-time fiddle, but I think they describe certain tendencies, strong enough to be ascribed to the very nature of this musical tradition and its performance.

I feel that my involvement in old-time fiddling has proven extremely beneficial for both my playing and sense of musicianship in general. In order to justify this assertion, I would like to examine a few aspects of old-time fiddling and make a few short comments. These comments will be based on my short old-time fiddling experience and some general views on skill development and the acquisition of knowledge. I am aware of course that by no means are they valid among all practitioners of old-time fiddle, but I think they describe certain tendencies, strong enough to be ascribed to the very nature of this musical tradition and its performance.

DOWNLOAD ALL ARTICLES ON OLD-TIME FIDDLING IN A SINGLE PDF FILE

Playing the “wrong” way

Old-time fiddlers very often adopt ‘unorthodox’* ways of playing the violin. ‘Unorthodox’ here will refer to approaches that on one hand do not satisfy the technical demands of what we can generally call ‘classical technique’ and on the other do not go beyond certain objective physical limitations. Playing the violin behind the back for example is indeed something possible (as several great performers have showed us) but it is no longer an unorthodox way of playing in the sense explained here.

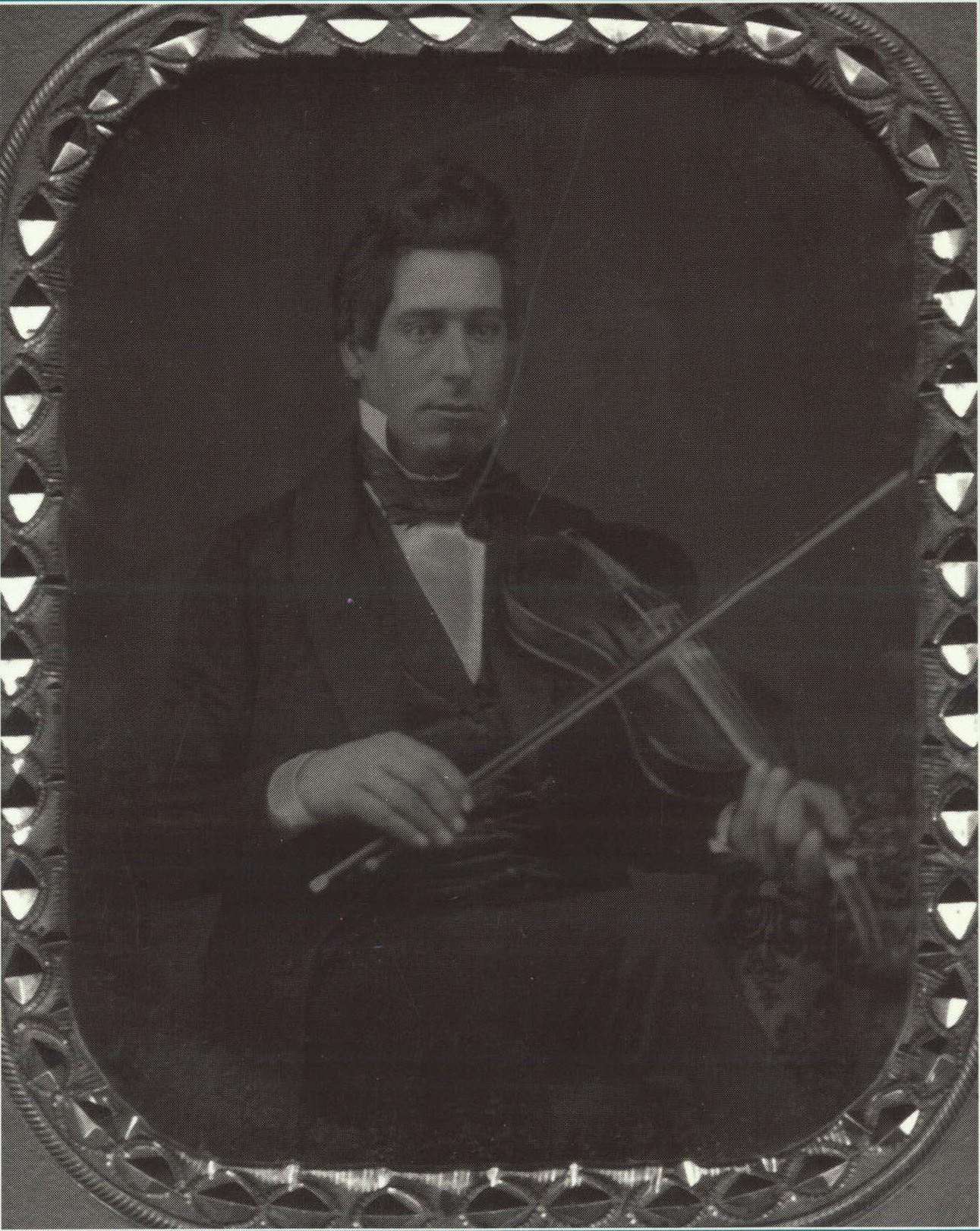

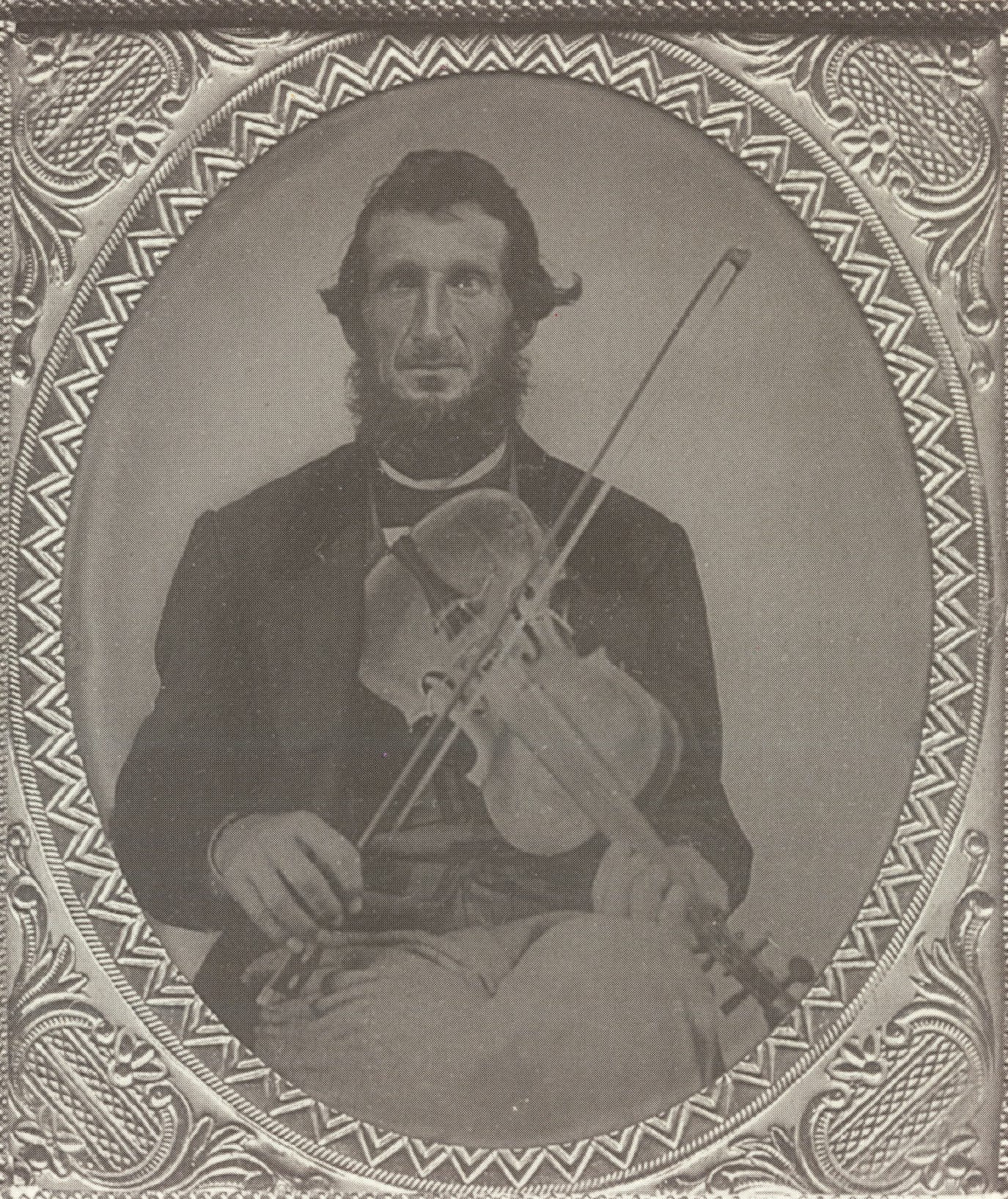

There are two striking habits that appear among a considerable number of old-time fiddlers: their tendency to hold the fiddle against their chest rather than the classical way, and their tendency to hold the bow in all sort of weird ways, often gripping it away from the frog. For a classically trained violinist the image of someone playing this way is alien. However, these habits among old-time fiddlers should not be seen as restricting or simply wrong. I believe they are deeply meaningful and rooted in legitimate stylistic and musical aspirations.

But why hold the fiddle against the chest? Since the biggest part of old-time fiddle repertoire requires playing only in the first position, shifting positions in old-time fiddling is not very common. There is even a tune called ‘Quince Dillons high D tune’ obviously named after the fact that the fiddler needs to shift in order to play a high D note on the E string. At the same time, it is widely held that holding the violin the classical way allows for easier changing of positions. And this is obviously true. But many folk fiddlers around the world do not really need classical techniques in order to be fair to their beloved musical traditions.

So one basic reason for why old-time fiddlers often hold the violin against their chest is simply because they do not have to hold it otherwise. Consequently, there is absolutely no point in criticizing and commenting on old-time fiddlers’ technique from a classical point of view. On the contrary, I believe that holding the violin against the chest in this tradition is an excellent manifestation of economy playing. It is a theory-free habit, which crystallizes through time and the need to play favorite tunes. And of course the idea of economy of physical effort is of great importance in learning an instrument.

Holding the fiddle against the chest also allows performers to have optimum visual contact with their fellow musicians and the environment, something which not only enhances musical communication but also creates a healthier, more intimate and organic relationship with what is going on around them. In addition, it enables them to have a good look at their instruments while playing, something which helps in monitoring technical elements like bowing, etc. (In classical music there is a stigma that if you have to look at your hands while you’re playing then you’re incompetent).

Holding the fiddle against the chest also allows performers to have optimum visual contact with their fellow musicians and the environment, something which not only enhances musical communication but also creates a healthier, more intimate and organic relationship with what is going on around them. In addition, it enables them to have a good look at their instruments while playing, something which helps in monitoring technical elements like bowing, etc. (In classical music there is a stigma that if you have to look at your hands while you’re playing then you’re incompetent).

Finally, it accommodates and develops the ability to sing while playing. This is a very interesting skill developed by some old time fiddlers, which may not seem useful for people involved in other musical traditions. For me it is a further sign of a wide ability to receive and respond to musical or non-musical stimuli while playing. Ask violin players to say a short phrase or answer a short question while playing something simple. I believe that in most cases their playing will collapse in a second.

It is a fact that a lot of old-time fiddlers have a wide capacity for incoming information during performance. This is not because they are talented or gifted. It’s simply because they operate within a musical tradition that encourages and calls for elements of communication and interaction during performance. Other musicians I have played with have such a narrow perception capacity, that they are unable to realize even on an elemental level what is going on around them musically and socially.

Being able to perceive, process and –even more so– to respond to information coming from outside is being able to interact musically and socially. It is an enviable performing quality and a big part of the whole musicianship discussion. I find it very interesting, worth investigating and developing.

As far as the variety of bow grips among old time fiddlers are concerned, they seemed to me very strange at the beginning, but in many cases these bow grips did not confine their musical goals in any crucial way. I think personalized bow grips largely originate in the need of old-time fiddlers to produce a percussive feel and effect with their bows, and to convey the dance feeling to their audiences. From that point of view, they constitute the bodily expression of a purely musical need rather then the implementation of a predetermined technical demand.

It is exactly this genuine and organic process that explains the development of a remarkably relaxed hand by some old-time fiddlers. I have come across old-time fiddlers whose right hand kinaesthetic quality would be envied by the average classical performer. And of course, the importance of a relaxed right hand while playing the violin cannot be overestimated.

There is also another broader implication that arises from this question of ‘unorthodoxy’. It can be compressed into these words by Christopher Small: A fish is not aware of the water, since it knows nothing of any other medium. In order to comprehend the nature of a certain principle, we must familiarise ourselves with the ‘different, ‘wrong’ or the ‘unorthodox’.

This is where I think the importance of the ‘unorthodox’ in old-time fiddling lies: The ways these people play represent a different source of empirical knowledge, experience and information, with which we have to acquaint ourselves and understand, in order to have that ‘binocular vision’ that the anthropologist Gregory Bateson has described as necessary for an all-embracing image of our world. Our two perspectives then come into a single, more reliable perspective according to Bateson’s principle that ‘two descriptions are better than one’.

This is where I think the importance of the ‘unorthodox’ in old-time fiddling lies: The ways these people play represent a different source of empirical knowledge, experience and information, with which we have to acquaint ourselves and understand, in order to have that ‘binocular vision’ that the anthropologist Gregory Bateson has described as necessary for an all-embracing image of our world. Our two perspectives then come into a single, more reliable perspective according to Bateson’s principle that ‘two descriptions are better than one’.

I have found a nice formulation of this concept on the web by Sylvia S. Tognetti in the section of her work on Gregory Bateson titled The value of diversity: Double descriptions are key to understanding relationships because these result from patterns of interaction that consist of stimulus, response and reinforcement, and provide a context for understanding behavior. I find this comment valid enough within a musical context. It explains why acquaintance with diversity is a key idea that can prove useful while learning how to play an instrument.

Herbert Whone also suggests a similar concept in his book The simplicity of playing the violin that can be applied in the learning process; it is called contraction and is the method of knowing a thing by its opposite. The student is encouraged to consciously adopt an unorthodox approach in order to comprehend and achieve what is considered as ‘correct’ or ‘desirable’.

This is in strong contrast with the incrimination of the ‘wrong way’ often present in violin methods and teaching approaches. Let’s take an example: I have met violin teachers who would happily place mines on the fingerboard on the ‘out of tune’ areas if they could, in order to prevent their students from experimenting. I think this is often the conceptual background of a ‘fixed’ performing attitude, which is reflected on the body language and, eventually, sound of the musician. Not to mention the fact that acquaintance with the audible relationship between random frequencies (and not just between ‘right’ frequencies) sharpens hearing and the ability to differentiate between in tune and out of tune.

Therefore, I would insist that in order to foster a free musical mind and body, a violin teacher should encourage students –according to the above idea– to freely explore the fingerboard, in order to familiarize themselves with the feel, the traps and the sounds of it. This kind of process can enable musicians to defend any performing or technical aspects of their playing, as opposed to slavishly following a purely dictated system.

Classical violin technique has of course its own rules and principles. They are the quintessence of human experience and laws of physics, and have good reasons to exist. (We should not forget of course that even within this framework of generally accepted rules there are different violin schools, like the Russian or the Franco-Belgian. There are even different bowing techniques in ‘authentic’ performances of early music, e.g. baroque, which involve different hand positions from the traditional classical/romantic way of playing). At the same time, they are also style-defining and therefore necessary only for those who are after the instrument’s maximum technical capabilities or certain sound qualities. These sound qualities are not necessarily ‘better’ than others and they certainly do not constitute a musical article of faith. Holding the violin the classical way is not really a prerequisite for playing or enjoying, since obviously not everyone is interested in learning how to play Paganini’s caprices.

Classical violin technique has of course its own rules and principles. They are the quintessence of human experience and laws of physics, and have good reasons to exist. (We should not forget of course that even within this framework of generally accepted rules there are different violin schools, like the Russian or the Franco-Belgian. There are even different bowing techniques in ‘authentic’ performances of early music, e.g. baroque, which involve different hand positions from the traditional classical/romantic way of playing). At the same time, they are also style-defining and therefore necessary only for those who are after the instrument’s maximum technical capabilities or certain sound qualities. These sound qualities are not necessarily ‘better’ than others and they certainly do not constitute a musical article of faith. Holding the violin the classical way is not really a prerequisite for playing or enjoying, since obviously not everyone is interested in learning how to play Paganini’s caprices.

The mosaic of individual approaches in old-time fiddling serves different musical ambitions, intentions and tastes. It represents a sizable reality in our musical world which cannot be ignored, and rightfully claims its stolen space of meaning and value next to everything else. It is not a threat to ‘orthodox’ violin technique, but explains it further, enriches it and probably questions it from time to time. In my mind, watching people adopting all weird approaches to playing the violin is charming on its own. Above all, it satisfies my strong instinctive need to see all the possible ways people do what I do, keeping my eyes and my ears thirsty.

If you found this post helpful and inspiring, the smallest contribution will encourage the author to continue writing and sharing his ideas.